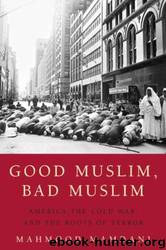

Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror by Mahmood Mamdani

Author:Mahmood Mamdani [Mamdani, Mahmood]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Religion, Islam, General, Social Science, Islamic Studies

ISBN: 9780385515917

Google: W69rBkP3W7QC

Amazon: B000FCK5V2

Publisher: Harmony

Published: 2005-06-20T16:00:00+00:00

But the absence of a stated CIA objective did not mean a lack of a clear CIA preference. Ironically, this objective was so central to U.S. policy that it led to a high level of tolerance for groups not particularly well disposed to the United States. As early as 1985, during a visit to address the UN, Gulbuddin Hikmatyar refused to meet President Reagan, arguing that “to be seen meeting Reagan would serve the KGB and Soviet propaganda,” which “insisted that the war was not a jihad, but a mere extension of US Cold War strategy.”

The seven resistance groups that made up the Afghan jihad were divided into two opposing political constellations, one traditional-nationalist, the other Islamist. Barnett Rubin has sketched their historical formation and political perspective in some detail. The leadership of the traditionalist bloc came from the historic elite of Afghanistan, who were either heads of the Sufi orders (the Qadariyya or the Naqshbandi tariqa) or traditional alims (legal scholars) versed in Islamic jurisprudence. None of these three mainstream groups received external assistance of any significance. The National Islamic Front of Afghanistan, led by the head of the Qadariyya Sufi order, was considered too “nationalist” and “insufficiently Islamic” to receive funds. The Afghan National Liberation Front was led by the family that headed the Naqshbandi tariqa. It was more of a centrist group that pledged both to defend “national traditions” and to establish “an Islamic society”; it, too, “hardly existed as a military force.” The only traditional-nationalist group with a military presence on the ground was called the Movement of the Islamic Revolution. Led by a respected alim who both ran a large traditional madrassah and controlled huge landholdings, its commanders (in particular, Mullah Nasim Akhundzada of the Helmand Valley) were also among the largest drug lords inside Afghanistan.

In contrast to these three traditional-nationalist groups whose leadership came from the historical tribal and religious elite of Afghanistan, leaders of the four Islamist groups came from students and faculty active in the Jamiat-i-Islami, the parent Islamist organization at Kabul University in the 1970s. The first split from the Jamiat came in 1975 and led to the formation of Hikmatyar’s Hizb-i-Islami (Hizb). A later split from the Hizb led to the creation of the Khalis faction. The fourth Islamist organization was led by Abd al-Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf, who had studied at Al-Azhar University in Cairo and then joined the sharia (law) faculty at Kabul University. He had been Burhaneddin Rabbani’s deputy in the Jamiat in the 1970s.

The key parties in the Islamist constellation were the Jamiat and the Hizb. After the split with Hizb, Jamiat had turned into the “main voice for non-Pashtuns, especially Persian speakers.” Jamiat field commanders were autonomous and retained control over their men’s weapons. Led by the most successful of the commanders, Ahmed Shah Massoud, Jamiat developed into “the most powerful party of the resistance” over the course of the war. In spite of that, the Jamiat was not the preferred recipient for CIA support. There

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19007)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12178)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8877)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6862)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6252)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5772)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5719)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5484)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5417)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5205)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5132)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5068)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4902)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4766)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4732)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4689)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4490)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4476)